CCXLVII

|

|

Treasure Island

|

As

the 1930s entered their latter half, Juan Trippe was understandably irked at

the world’s only transoceanic airfield, as well he should have been. He owned

it. Or at least he rented it from the U.S. Navy. It was a strictly utilitarian

flying boat base at Alameda Point on the Oakland Estuary built in 1927 when the

wetlands were filled in and an East-West runway and three hangars were

constructed. A series of nineteenth century ship hulks, including some of Civil

War vintage, were sunk offshore to create a breakwater. The area soon became

known as the “Yacht Basin” and in 1930 the United States Army Air Corps, which

controlled it then, named the complex Benton Field. A few wooden barracks

buildings and prefabricated metal structures popped up over time but Benton

Field was underutilized.

|

|

The Yacht Basin

|

The

Army gave Benton Field to the City of Alameda, who in turn handed it over to

the Navy for management. Since the Army, the Navy, and the City of Alameda all

used Benton Field, but none of them very much, it was difficult to say who had

the ultimate responsibility for it.

|

|

The China

Clipper (NC14716 or “Sweet Sixteen”) undergoing maintenance at Alameda

|

When

Juan Trippe came looking for a Pacific Coast homeport for his flying clipper

ships, the Yacht Basin seemed a perfect, if strictly temporary, spot. The area

was just large enough to land and moor the M-130s and the S-42Bs that Trippe

expected would serve as the backbone of his Pacific service. Plus, it was

cheap. Trippe paid the Navy a nominal rent as an old Naval Aviator might, and

ignored the tangle of Army and Municipal interrelationships he might otherwise

have had to address.

|

|

A Municipal plan showing development along the

Estuary

|

The

China Clipper first left Alameda on

November 22, 1935, and for the next year carried out survey flights and carried

mail and cargo only, as Trippe reached across the sea step-by-step. The cargo

crates and mail sacks could have cared less about the flaking paint on the

barracks or the rust spots on the prefabs, or the general air of untidiness that

pervaded the site, but long before passenger service began on October 21, 1936,

Trippe knew he needed to upgrade.

|

|

With little raw material to work with on the

ground, Pan Am could only point out that Alameda’s facilities were “temporary”

and had “attractive signs”.

|

The

problem was that there was no immediate upgrade available, so Pan American

tried to put lipstick on a pig. Even with a fresh coat of paint, a comfortably

redecorated “terminal” and a bar and grill on site, Alameda still had all the

charm of the back side of a strip mall. The hulks poking up through the water

in the bay like so many broken teeth only added to the seedy atmosphere.

|

|

The crew of Sweet Sixteen prepares for their

first departure from Alameda as an excited crowd looks on

|

Pan

American Airways wanted anything but to be seen as seedy. The whole brand was

predicated on glamour, but their decidedly unglamorous China Clipper facilities

spoiled the effect even before the effect took hold. Honolulu and Midway and

Wake and Guam and Manila might all be tropical and exotic and replete with

shrimp cocktails and umbrella drinks, but the promise of Alameda was the

promise of a per-the-hour motor hotel.

|

|

During World War II Benton Field became known

as Alameda Point Naval Air Station and was greatly expanded. The Yacht Basin

was landfilled and the Pan Am facilities were torn down. Hangar 14 was

decorated with a Pan Am logo in honor of the airline’s connection to the site,

but the hangar was never used by Pan Am despite local urban legend

|

As

always, Juan Trippe had a plan. As almost always, he kept it to himself. It

focused on a place called Treasure Island, a place that didn’t even exist yet

when the China Clippers first took to the skies.

|

|

The China

Clipper calling at Alameda with the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge in the

background

|

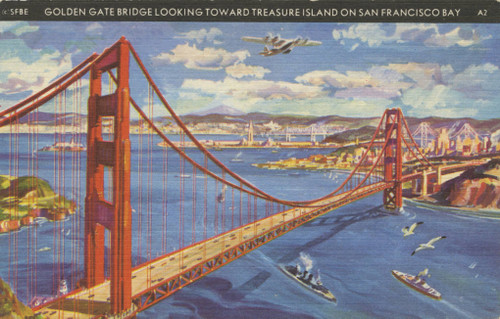

San

Francisco, like Pan American Airways, was growing into itself. In 1935, the

China Clippers linked San Francisco to the Orient by air for the first time. In

1936, the White City By The Bay celebrated the opening of the San

Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, and in 1937, it celebrated the opening of the

Golden Gate Bridge, then the world’s largest and longest suspension bridge. To

cap this era of civic growth and pride, the city fathers planned The Golden

Gate International Exposition. It was slated for two summer seasons 1939 and

1940, it was meant to celebrate San Francisco, and not coincidentally, it ran

at the same time as the New York World’s Fair of 1939-1940.

|

|

A China Clipper takes to the air over the

Golden Gate Bridge

|

After

reviewing several sites and finding none of them suitable, the city decided to

enlarge Yerba Buena Island in the bay, landfill the Yerba Buena Shoals, and use

the reclaimed land for the Exposition.

|

|

The map to Treasure Island

|

The

resulting island was just under a mile square and was accessible by ferry. A

large part of the cost was borne by the Works Progress Administration, with

smaller sums being contributed by the State of California, the City of San

Francisco, private donors, and corporate sponsors, including Pan American.

|

|

Pan Am’s hangars under construction on Treasure

Island, 1937

|

Juan

Trippe casually suggested to the Exposition’s directors that the island could

be used as a municipal airport following the close of the Fair. The plan received

dynamic endorsement, and Trippe had a permanent home for the China Clippers. A

permanent Administration Building costing one million dollars and two hangars

were constructed thereafter, with much of the cost spread between the funding

sources.

|

|

An artist’s conception of Treasure Island as an

aerodrome

|

In

laying out his proposal to the city, Trippe made sure that the overall cost of

transforming the fairgrounds into an airport would be modest. The fair’s wide,

well-paved midway (called the “Gayway”) was given the dimensions of a runway,

and the secondary paths were constructed with their use as taxiways in mind. A

marina was built on the south end of the island with mooring facilities for

flying boats. The space between Yerba Buena Island and Treasure Island was

named Clipper Cove.

|

|

Pan Am’s Treasure Island Airport, imagined 1938

|

The

most memorable structure of the Exposition was the 400 foot tall Tower of the

Sun with its reflecting pool, which became the symbol of the fair.

|

|

The Tower of The Sun, Treasure Island, 1939

|

Sadly,

much like the New York World’s Fair which was in progress on the east coast,

the Golden Gate International Exposition lost significant money. The public

mood was growing darker by the day. By the time both Fairs opened for their

first seasons in the Spring of 1939, the shadow of war had nearly waxed full.

Autumn would see virtually all the world at war except the United States of

America, leading to calls for cancellation of the second season of both Fairs.

They went on regardless in 1940, ghost towns celebrating a world that was

vanishing by the moment.

|

|

The Trylon and Perisphere, Flushing Meadow, New

York, 1939

|

The

war was to disrupt and destroy many plans and lives, and it would change the

trajectory of Pan American Airways in ways which Juan Trippe never could have

imagined.

|

|

Dusk for the Tower of the Sun. With the ending

of the Exposition Pan Am moved into what the airline thought would be its

permanent home on the Pacific coast. The landplane airfield was fated never to

be completed, but the remaining M-130s, S-42s, and new Boeing 314s (shown) used

Treasure Island as their base for a single brief year until the World War

changed everything

|

No comments:

Post a Comment