LXXIX

|

|

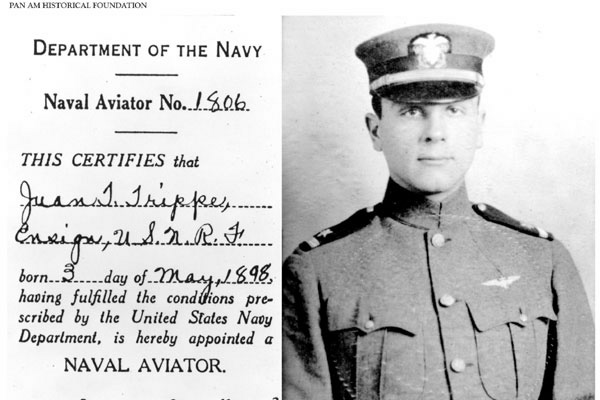

Juan Trippe, Naval Aviator without a

cause, 1918

|

Juan Terry Trippe, newly-minted Naval

Aviator U.S., watched a little forlornly from the fantail as his troop

transport's wake left a vast "U" atop the ocean's surface. Trippe was

headed back home, his particular services no longer needed. News of the

Armistice had come when the ship was in the mid-Atlantic, and the skipper had

turned her, maybe a little too enthusiastically, Trippe thought privately, back

toward New York.

Trippe wasn't sorry that the war had

ended. Nobody was. Too many good young men had died for anyone to feel anything

but relief. But mixed in with that relief was just the slightest tinge of

disappointment. Juan Trippe had missed his war by an inch.

The truth is, he probably wouldn't have

made it into the war at all but for his family connections. Juan was a Yale

man, and a somewhat Johnny-Come-Lately member of the Yale Aero Club. All of the

founding members, including his friend and classmate, the now-lionized Dave

Ingalls, had become members of "Yale Unit One," and Yale Unit One had

volunteered to a man for training in the completely new field of Naval

Aviation. Just as the Army had its Air Corps, the Navy had its Aviators. Interservice rivalries being what they were, the Marines (technically part of

the Navy, despite a long history apart from the Sailormen they despised so

much) wanted Airmen too.

Juan liked the Marine dress uniform,

the white cap, and the Mameluke sword. He liked the Old Breed honor of the

Marines. So, unlike Dave (now the Navy's first combat Ace, with five kills and

a fund of hair-raising war stories), Juan volunteered to be a Marine Airman.

And promptly flubbed out when he failed

the eye test. That was the end of the Marines for Juan, but his father called

the Secretary of the Navy, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, an old friend despite

being a Democrat, and Juan managed to pass the eye exam for the Navy. So, like

Dave, he was now a Navy Man, though Juan was eighteen months behind him. Still,

the Trippes usually got what they wanted.

|

|

The State Flag of Maryland showing the

Calvert Arms

|

And always had. The Trippes were a

cadet branch of the Calvert clan, the colonial family that had founded

Maryland. Maryland's state flag still bore the Calvert arms. Lord Baltimore was

a close relative. The Trippes had settled on the Eastern Shore around the

little river they named for themselves, Trippe Creek, and had gone into tobacco

plantation and slaves.

Unlike most Southern planters, the

Trippes looked North as much as they looked South, and got involved in building

and owning Baltimore Clippers in the 1820s. When the Baltimore Clippers

transmogrified into full-sized Clipper ships in the 1840s, the Trippes went

along for the ride, building and owning them too, and shipping commodities ---

especially tea --- in them.

The family had, of course, split during

the Civil War, but most of the Trippes, with their Yankee sailing connections,

had sided with the North. By the time Juan was born (in 1899, despite the date

of his Aviator's Certificate) the family was staunchly Republican, obscenely

rich, and deeply involved in investment banking.

Juan, despite his forename, had not a

drop of Latino blood in him. His parents had named him after a deceased

relative-by-marriage who had done much to bring democracy (and free-market

capitalism) to Cuba when it was still a colony of Spain. Juan cordially hated

his name. Among his white-bred peers his name raised eyebrows, and so Juan

often found himself an outsider. Spending more time alone than was strictly

good for himself, Juan liked to imagine himself a clipper captain battling the

raging seas. He'd been born a little too late for that (and among the Trippes

it was just not "done" --- the family weren't captains, they hired

captains), but Juan found fulfillment of his romantic fantasizing in the idea

of flying.

|

|

A Baltimore Clipper

|

Except now it looked as though he wasn't going to be doing any of that either. He knew what was coming. He would take whatever task the Navy assigned him now (though he suspected correctly that another call from his father to Secretary Roosevelt would see him mustered out within days), and then it would be back to Yale to finish his degree. Then it would be the family business.

|

|

A tea clipper

|

Juan finished his Yale degree as he was

supposed to and went to work in the family's investment bank on Wall Street as

he was supposed to, but by 1922, he was sick of it all. "Work"

consisted of appearing at the office at midmorning, making a raft of telephone

calls to familiar investors (usually wealthy friends and relatives or wealthy

friends and relatives of friends and relatives) and cajoling them into buying

stock. They almost never said no. Luncheon, a five martini affair, came around

one P.M., and then the younger men were off to the golf links or the tennis

courts or the yacht club to talk business and brag about their new cars or

girlfriends, or wives and mistresses. It was all very safe, and very vapid, and

Juan hated it. He remembered the freedom and romance of flying, and he wanted

that.

So he began to pitch his friends a new

investment, Long Island Airways, meant to fly the rich and powerful from their

Gatsbyeque lives on the North Shore of Long Island to their faux-Maritime lives

in the Hamptons. He purchased a number of Navy-surplus seaplanes and a couple

of Jennys. His family was horrified that he sometimes climbed into the cockpit

and took the controls ("We aren't

captains, we hire them!") but he was flying again, and he loved it.

During the week, when the Hamptons were

quiescent, he used Long Island Airways to give inexpensive sightseeing tours

over Long Island, New York City, and New England. His people accused him of

being a barnstormer, but Juan didn't care. He was discovering that the hoi polloi loved flying as much as he

did.

Perhaps worst of all from the family's

perspective, he and his pilots hired out to shoot movies with Astoria Studios

in Queens. Astoria Studios produced a lot of silent-movie romances about daring

young World War I aces who got the girl (or augered in, breaking the girl's heart)

and Juan, stunting and diving over the potato fields of Long Island or the

hills of the Berkshires in Massachusetts, sometimes appeared on film, incognito

behind his goggles and leather flying helmet. Airplanes remained an audience

fascination for years. In 1927, the first Academy Award for Best Picture was

given to the film Wings.

|

|

Woolsley-Astoria Studios around the

time Juan Trippe was a flying stuntman for them. Today, they are

Kauffman-Astoria Studios and among many other shows, they provide a home to Sesame Street

|

Long Island Airways made enough money

so that Trippe was able to expand it within three years. In 1926 it became

Colonial Airways, providing the first shuttle service between New York and

Boston. He also got his first U.S. Mail contract. Eventually, he sold Colonial

to buyers who turned Colonial into American Airlines.

By then, Juan Trippe had moved on to

even bigger things.

|

|

Colonial Airways at Logan Airport,

circa 1925

|

No comments:

Post a Comment