LXVIII

It was starting to rain more heavily

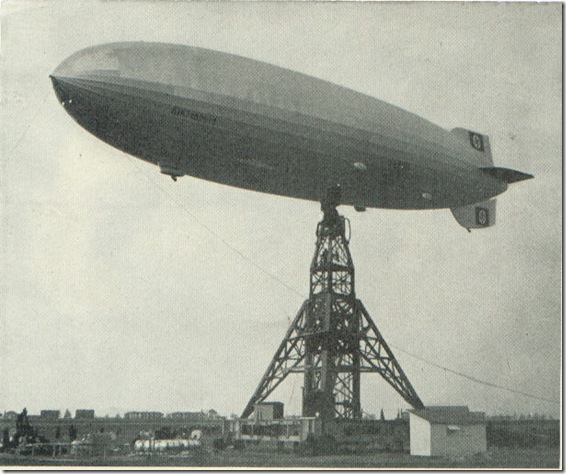

again as at 7:17 P.M. on May 6, 1937, the Hindenburg

moved into position near the mooring mast at Lakehurst N.A.S.

|

|

At 7:19 P.M on May 6, 1937, the Hindenburg dropped water ballast three

successive times as she tried to correct her trim. Her tail-heaviness is just

about noticeable in this picture

|

The ship was planning on accomplishing

a "flying" moor or a "high" moor, where it would be tied to

the mast while in flight and then winched down to the ground. It was a

technique the Americans had used regularly with the Shenandoah, the Los Angeles,

the Akron and the Macon, and, for that matter, with the Graf Zeppelin and the Hindenburg itself several times. It was

not the Germans' usual, or preferred, landing technique.

A sudden gust of wind pushed the big

dirigible out of its proper docking alignment.

According to "the book" the

Captain should have moved off, circled the field, and lined up again, but such

a maneuver would take about twenty minutes, a precious fragment of time in the Hindenburg's tight flying schedule.

And there was no guarantee that another

gust of wind wouldn't gum up the works again.

The ship still had to land its

passengers, refuel, reprovision, take on new passengers, lift off, fly to

Germany, repeat the process, and then repeat it again to reach London, all by

May 11th so that it could undertake its own questionable participation in the

Coronation of the new British monarch.

Of course, Pruss and Lehmann and the

other three captains aboard seemed to overlook one factor, that if the Hindenburg left Lakehurst in a timely

fashion --- it didn't have to be the helter-skelter one Pruss was set on --- it

would pick up the headwinds it had battled coming westward. Only now they would

be tailwinds speeding the ship toward Europe. There was every chance the Hindenburg could regain the twelve hours

it had lost.

But it never seemed to occur to anyone.

Captain Pruss decided to ignore the

book. He ordered hard-a-starboard, and the ship veered --- very hard, in what

has been described as a tight "S" --- over toward the waiting mooring

mast. It was 7:18.

This wasn't a misdemeanor, a felony, or

even an invitation to disaster. After all, there was nothing in the book about flying

blind through the Stanovoy Mountains, tipping a ship on its tail and then its

nose to overfly electrical wires that could have caused a mass-destruction

event, or traveling to the North Pole, and Dr. Eckener had done all of that in

the Graf Zeppelin.

But Pruss wasn't Eckener and the Hindenburg was not the Graf Zeppelin.

A few moments later, the ship's

commutator showed her down at the stern. Pruss ordered hydrogen valved from the

bow, and then three ballast dumps totaling nearly 3,000 pounds of water, over

the next minute in order to bring the ship level. When nothing seemed to work,

he ordered a half-dozen men into the nose. Finally, at about 7:20, she evened

out.

|

|

7:20 P.M.: A seaman giving directions

to Captain Pruss as the Hindenburg

nears the mooring mast. Note the assembled ground crew

|

What had happened should have alerted

the bridge to a very serious problem. Somewhere aft the ship was losing

buoyancy. And it was losing buoyancy because it was losing hydrogen. But,

oddly, no one on the bridge recognized the problem.

Pruss went on trying to land his ship.

If anything could have been done to save her, the opportunity was leaking away

by the moment along with the ship's lifting gas.

It was at this point that people on the

ground noticed an odd "flutter" at the very top of the ship's

envelope just ahead of her upper vertical stabilizer. A few wondered what it

was. Fewer realized that they were watching lighter-than-air gas escaping

through the Hindenburg's fabric skin.

At 7:21, Pruss ordered the hemp mooring

lines dropped from the nose and the stern. The ropes snaked down through the

rain and landed with splatting noises as they hit the drenched earth. After a

few moments, the ground crews picked them up and began working with them. They

were pulling the ship toward the mast. They made her fast and began to winch

her down toward the ground.

From the gondola, Captain Pruss waved to

Commander Rosendahl who had come outside to watch the landing. Waiting family

members called up to familiar faces at the Promenade windows. The ship was

coming closer to the ground.

|

|

7:25

P.M.: The last known photograph of the intact Hindenburg. Note the mooring line trailing from the bow

|

Four minutes later, they all heard a dull pop, "like the burner of a gas stove being switched on."

|

|

An

eyeblink later . . .

|

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete