LXXXVII

|

|

One of Pan American's earliest Fokker

Clippers lifting off in poor weather from Meacham Field, Key West, Florida in October

1927

|

|

|

One of the last Pan Am flights, a local

shuttle "Express," lifted off from Key West in December 1991. Of the “Pan Am Express” planes, only the

first, Clipper Commodore, had a name.

It was not a good omen for the airline

|

The name "Rockefeller" is

synonymous with wealth and power. Juan Trippe knew this as well as anyone, and

he invited a Rockefeller to invest in Pan American Airways. This same

Rockefeller (William) was a member of Pan Am’s original Board of Directors.

John D. Rockefeller, the nineteenth

century paterfamilias of the clan, rose from obscure grain merchant to the head

of the mightiest of American corporations, Standard Oil (today's Exxon Mobil).

Although John D. Rockefeller was the public face of Standard Oil, Rockefeller

had a partner who kept the books and managed the backroom deals, and may, in

fact, have been more responsible for Standard Oil's financial success than

Rockefeller himself. He was named Henry Morison Flagler, hardly a household

word, hardly even in South Florida, but he created the conditions that allowed

Pan American Airways to thrive.

|

|

John D. Rockefeller, the Master of

Standard Oil

|

|

|

Henry Morison Flagler was Rockefeller's

partner in Standard Oil, and was the true businessman of the pair. He was a

cutthroat henchman who acted as a lightning rod for Standard Oil's perceived

evils

|

|

|

When Flagler came to Florida he fell in

love with the State. He built The Breakers in Palm Beach as a hotel for his

visiting friends

|

By the time Flagler was fifty five he

was one of the wealthiest men in the world. He had a deserved reputation as a

cutthroat robber baron, and had been investigated by Congress and denigrated in

the press for his greed. Yet, at fifty five, the trajectory of Henry Flagler's

life changed completely. In an attempt to ease his first wife's chronic asthma,

he left his sprawling Westchester County, New York estate, (bizarrely called

"Satan's Toe"), and came to St. Augustine, Florida, America's oldest

city, where the perpetual summer of Florida eased Mrs. Flagler’s breathing. It

was when Flagler saw his first palm tree that the stoic business tycoon's heart

thawed. He fell in love with Florida passionately, the way some men fall in

love with women. He built a house in St. Augustine, laid a railroad, and then

built a resort hotel for his friends and associates so they too could enjoy

Florida. Captivated by the countryside, Flagler traveled down the coast until

he found what he deemed to be paradise --- and in his own private Xanadu this

Kublai Khan a stately pleasure dome decreed.

|

|

Worth Avenue in Palm Beach is a street

of exclusive shops. Cartier started out making timepieces for pilots

|

That pleasure dome still stands. It is

called Palm Beach, now one of the wealthiest cities in America. And here too,

Flagler stretched the railroad and built a resort hotel, the massive Breakers,

still one of the nation's most imposing hotels.

|

|

West Palm Beach, the poorer relation,

seen across Lake Worth, circa 2016

|

When Flagler built Palm Beach he also

created the class structure of Florida. The rough service camp of the workers

who actually built Palm Beach lay 500 yards across Lake Worth. It later became

known as West Palm Beach. Until the year 2000, West Palm Beach was the exact opposite

of glittering Palm Beach. West Palm Beach was a ramshackle city hardly fit to

be the County Seat of the largest and wealthiest of Florida's 67 counties. In

2000, a local West Palm Beach judge, later known ruefully as "Hanging

Chad," gave the Presidential election to George W. Bush, who rewarded West

Palm Beach with a blank check for urban renewal. The shanties along the

railroad tracks vanished, and a city of boutique shops, fine restaurants, and

recreation venues replaced them seemingly overnight, despite a flailing economy

and a post - 9/11 numbness, which still lingers. Now, West Palm Beach, though

still the poorer relation, has moved from the room over the toolshed into the

guesthouse.

|

|

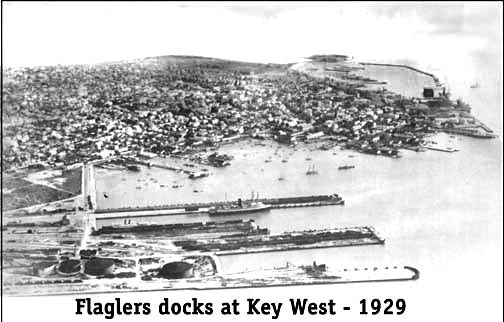

Flagler's Key West docks. Henry Flagler

imagined Key West as the southern gateway to the United States

|

Having built Xanadu, Flagler looked

around for more worlds to conquer. Rather than going West, he went South,

giving a rail connection to sleepy Fort Lauderdale. Further to the South, an

enterprising woman named Julia Tuttle, who owned most of the land around an old

frontier post named Fort Dallas, traded her land to Flagler for a rail line and

urban improvements. The grateful citizens of Fort Dallas vowed to rename their

tiny town "Flagler" after their benefactor, but Flagler modestly

insisted that the city be named for the local native American tribe who'd lived

along their namesake Miami River.

Having reached Miami, Flagler saw no

reason to stop building. At that time, the late nineteenth century, Key West,

on faraway Bone Island, was the largest city in Florida, a strange outlier

where smugglers, South American insurrectos

on the lam, and motor launch pirates lived cheek-by-jowl with cigar

manufacturers, fishermen, artisans, and artists. And though Bone Island lay

about 125 miles across mostly open water dotted by small points of coral and

populated by a hardy and independent folk who called themselves Conchs

(pronounced "Konk"), Flagler imagined steel rails leaping over the

ocean to connect Key West to the mainland.

|

|

Flagler's Overseas Railroad

|

1903 was a time of giant dreams. In

Great Britain, Ismay and Harland & Wolff were blueprinting that trio of

vast ships they called Olympic, Titanic and Gigantic. At Kitty Hawk, the Wright brothers took flight. Far south

of Florida, the Panama Canal was a-building. Flagler imagined that Canal

transshipments would use bustling Key West as their main port if only items

could be easily moved up the line. Havana, too, could be linked to Key West by

a twice-daily steamer so the exotic tropical fruits of Cuba could be delivered

by rail to New York in 48 hours.

The building of Flagler's railroad

across the sea echoes the creation of the Panama Canal. Both construction

projects took place almost simultaneously and faced similar hurdles. Much of

the right-of-way for Flagler's train line had to be laboriously hacked out of

mangrove swamp jungle and sawgrass wilderness, a Carboniferous Era world that

was teeming with billions of malarial mosquitoes, scorpions, wolf spiders, and

natural gas spouts, punctuated by Mesozoic Era alligators and snakes, a world

where man did not belong and few men had ever ventured. Flagler's surveyor,

William Krome, was nearly lost trying to chart a path through mainland Monroe

County (an area bigger than Rhode Island with a population numbered just around

one hundred even today). And even when a path was found, the unexpected kept

happening (Lake Surprise was named for a very simple reason).

|

|

Men laying track south of Homestead,

Florida, circa 1906. Although Flagler imagined the building of his railroad to

be a straightforward proposition, Florida balked at being scarred. Sometimes

rails sank into the soft ground and disappeared

|

But where the builders of the Panama

Canal were attempting to join two bodies of water, the builders of the railroad

were trying to join two bodies of land. The Florida Keys stretch in a

languorous arc southwestward away from the mainland. There are hundreds of

Keys, the remnant outcroppings of a long-extinct coral reef. The main arc is

made up of perhaps three score larger islands, separated in places by channels

narrow enough to jump across, and in other places by gaps as wide as seven miles.

The Keys have almost no natural fresh water sources, some were covered

completely in jungle, and others were practically deserts surrounded by a

turquoise sea. All supplies had to be brought in by rail and boat, and new

bridgebuilding techniques devised on the fly. Seven Mile Bridge is a wonder,

for at its midpoint one might as well be in midocean; no land is visible,

except a tiny key or two paralleling the road.

Conditions along the line were rough,

right down to the officially invisible floating bawdy houses that lay moored

offshore of the Keys (and Panama, too, for that matter; it's quite likely that

some of the same men worked both projects and shared the company of some of the

same ladies in both locales).

Marathon, Florida got its name because

Flagler promised his workers huge bonuses if they could reach the Seven Mile

Channel by a fixed date. It was a race they won. Flagler’s dominance in Florida

was so great that the old abbreviation for Florida, "FLA" was said to

be an abbreviation for "Flagler."

There were serious setbacks. While the Panama Canal had massive landslides in the Culebra Cut that swallowed work camps full of men whole, and then required duplicating the work of digging out amidst the corpses of the unlucky, the railroad faced hurricanes that did the same, and required the same rebuilding of the line under the same duress. By odd chance, the hurricanes of 1906 and 1908 both struck the line at its point of furthest progress, hurling building supplies (and men) into the ocean and testing (and damaging) the areas just under construction. Much had to be replaced and rebuilt and made stronger, but as time passed, it was time that became the great enemy, for the aging and ailing Flagler wished to ride his rail into Key West before he died.

Flagler got his wish in January of

1912, but his vision of Key West as America's major southern seaport never came

true. Mobile and Tampa and especially New Orleans became the great harbors of

the Southern Tier. Key West, crammed onto its tiny isle, had no place to grow.

As a result, Flagler's East Coast Railway never carried the freight it might

have, and went into receivership some years after his death in 1913. Still, it

was a popular rail line for tourists who as of a winter's day, as it was said,

could board the train in a snowbound New York and wake up in the tropics two

days later with a view of nothing but blue sky, white clouds, and a bluegreen

sea framed by palm trees.

|

|

The Overseas Railroad. Another

"Eighth Wonder of The World," it functioned from 1913 to 1935

|

|

|

The Hurricane of 1928 didn't touch the

Keys, but it was vicious enough to propel a 2 x 4 straight through a palm tree

in Lake Ocheechobee. Juan Trippe worried that Key West could be disastrously

cut off from the rest of the world by such a storm and made plans to move Pan

Am off the island

|

|

|

The destruction of the Overseas

Railroad in 1935 was world news. Even this Soviet magazine covered the disaster

--- quite accurately too

|

|

|

A remnant of the Overseas Railroad

standing next to the Overseas Highway

|

The Florida East Coast Railway was

central to Juan Trippe’s plans in 1927. As the only feeder line to Key West, it

carried most of the mail bound for Cuba and points south (there was a minimal

amount carried by packet boats from the mainland). The Category 5 San Felipe

Segundo Hurricane of 1928 on September 17th of that year didn’t even

brush the Keys, though it caused nightmarish havoc up around Lake Okeechobee,

killing at least 2,500 people. The rail connection to Key West was interrupted

briefly.

Trippe could do nothing about

hurricanes themselves, but the break in contact with the mainland made him

cognizant of just how isolated Key West really was (and is), Trippe had already

begun to consider just how crowded and small Key West could sustain the

infrastructure for his growing airline (by 1928, Pan Am owned eight Trimotors,

Fokkers and Ford “Tin Lizzies”). He decided to make plans to relocate Pan American

further north, in Miami. The move was fully completed by 1931.

|

|

Parts of the Overseas Highway date back

as far as 1905, and were used as service roads for the Overseas Railroad. In

1935, the Florida East Coast Railway sold the Overseas Railroad to the State of

Florida. Building the motor road became a Works Progress Administration (WPA)

project during the Great Depression.It has been continuously improved since

then

|

|

|

Seven Mile

Bridge

|

|

|

Key West International Airport today.

The runway is one of the shortest serving jets at an international airport and

planes must lift off at a steep angle

|

It was a prescient decision. On Labor

Day 1935, the most powerful hurricane ever to hit the United States tore

through the Upper Middle Keys packing winds of over 200 miles per hour. The

barometer dropped as low as and probably lower than 26.35. Keys residents and

visitors unfortunate enough to be caught by the storm (which had not been

forecast) were killed in the hundreds. Bodies of residents were found 40 miles

from their homes, having been carried there on the winds. Twenty years later,

three cars belonging to long-missing tourists were unearthed with their

skeletonized occupants still inside. The storm unleashed a tsunami estimated to

have been anywhere from 20 feet to 40 feet in height that washed away all the

trackbed in the Middle Keys and derailed the cars of the rescue train sent to

save who could be saved (the engine, weighing in at over 300,000 pounds

withstood the wall of water without toppling over).

The keening winds sounded a tocsin for

the FECRR. Without assets to rebuild, the railroad sold its rights to the State

of Florida which built the Overseas Highway to Key West. Nowadays, it is just a

few hours drive between Palm Beach and Key West, though a cautious driver who

keeps his eyes on the road misses much of the grandeur of the trip. Built in

places atop the rail line and in places parallel to it, the Overseas Highway

overlooks the gallant ruins of what is now known as "Flagler's Folly.”

|

|

The passenger terminal at Key West

International Airport. In 1982 the Conchs of the Keys, always a brawn lot,

"seceded from the Union" over a tax dispute, and declared themselves

the Conch Republic (Republica de la Concha). They maintain the Conch Republic

as a tourist attraction and now claim all the territory of the State of Florida

from Skeeter's Last Chance Saloon in Florida City, Florida southward as

sovereign Conch territory. It’s nothing new. During the Civil War, Key West

actually seceded from the Confederacy back into the Union

|

|

|

Juan Trippe's Key West docks. The

historical marker at Key West International Airport (then Meacham Field)

|

good stuff!

ReplyDelete